| A Study of Contrasts | ||||||||||

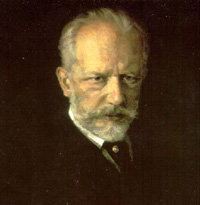

Symphony No. 5 in E minor, Op. 64 Throughout his creative career, Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky's inspiration went through extreme cycles, tied to his frequent bouts of deep depression and self-doubt. In mid-May 1888 he wrote to his brother Modest that he was convinced that he had written himself out and that he now felt neither the impulse nor the inclination to compose. By the end of the month, however, he set about "...getting a symphony out of my dulled brain, with difficulty." Inspiration must have started to flow, for by the end of August, the massive Fifth Symphony was finished. As was the case with most of Tchaikovsky's compositions, the premiere of the Symphony – in St. Petersburg, with the composer conducting – earned mixed reactions. The audience liked it, critics panned it and fellow-composers were envious. Modest believed that the problem with the critics lay with his brother's lack of confidence as a conductor. Tchaikovsky himself, however, was never at ease with the Symphony, and wrote to his benefactress, Nadeja von Meck: "Having played my symphony twice in St. Petersburg and once in Prague, I have come to the conclusion that it is a failure. There is something repellent in it, some exaggerated color, some insincerity of construction, which the public instinctively recognizes. It was clear to me that the applause and ovations were not for this but for other works of mine, and that the Symphony itself will never please the public." For the rest of his life he felt ambivalent about its merits, although after a concert in Germany, where the musicians were enthusiastic, he felt more positive. The mood of the entire Symphony is set by the introduction, a somber motto in the clarinets that reappears throughout the work and hints at some hidden extra-musical agenda,  a quote from a trio in Mihail Glinka's opera, A Life for the Tsar, on the words "Turn not into sorrow," Perhaps the motto reflects the melancholy and self-doubt Tchaikovsky experienced when he started composing the Symphony; certainly its mood is maintained throughout most of the work, where it casts a pall over whatever it touches. Some biographers have identified it with the Fate motive that appears throughout the Fourth Symphony, which is unrelentingly pessimistic. In the Fifth, the reincarnation of the motto from e minor to E major at the end of the Finale suggests the composer's reversal to a more positive frame of mind. The first theme is a resolute march, almost a grim procession through adversity. a quote from a trio in Mihail Glinka's opera, A Life for the Tsar, on the words "Turn not into sorrow," Perhaps the motto reflects the melancholy and self-doubt Tchaikovsky experienced when he started composing the Symphony; certainly its mood is maintained throughout most of the work, where it casts a pall over whatever it touches. Some biographers have identified it with the Fate motive that appears throughout the Fourth Symphony, which is unrelentingly pessimistic. In the Fifth, the reincarnation of the motto from e minor to E major at the end of the Finale suggests the composer's reversal to a more positive frame of mind. The first theme is a resolute march, almost a grim procession through adversity.  A second beautifully orchestrated theme reveals how many ways there are to represent a sigh in music. A second beautifully orchestrated theme reveals how many ways there are to represent a sigh in music.  The second movement, marked Andante cantabile, contains one of the repertory's great horn solos, The second movement, marked Andante cantabile, contains one of the repertory's great horn solos,  followed by a more animated theme for solo oboe. followed by a more animated theme for solo oboe.  The middle section of this ABA form features the clarinet in yet another poignant theme, The middle section of this ABA form features the clarinet in yet another poignant theme,  broken up by the tragic motto broken up by the tragic motto  before a return to an embellished version of the opening themes. before a return to an embellished version of the opening themes. The third movement, a waltz based on a street melody the composer had heard in Florence ten years before, also has an undertone of sadness, and towards the end the somber motto is again heard,  & &  the mood continuing into the Finale. the mood continuing into the Finale. The last movement presents the motto as the focal point of a final struggle between darkness and light, symbolized by the vacillation between its original E minor and E major.  The stately introduction mirrors the opening of the piece, although in an ambiguous mood and mode. The stately introduction mirrors the opening of the piece, although in an ambiguous mood and mode.  With the Allegro, the key returns decidedly to the minor, but the tempo picks up into a spirited trepak, a Russian folkdance. Finally, following a grand pause, the key switches definitively to E major – With the Allegro, the key returns decidedly to the minor, but the tempo picks up into a spirited trepak, a Russian folkdance. Finally, following a grand pause, the key switches definitively to E major –  with great pomp and fanfare – for a majestic coda based on the motto and a final trumpet blast of a version in E major of the first movement march. with great pomp and fanfare – for a majestic coda based on the motto and a final trumpet blast of a version in E major of the first movement march.  | ||||||||||

Piano Concerto in F Arranged And expanded for Jazz Trio and Orchestra by Marcus Roberts Jazz evolved in New Orleans in the early part of the last century from ragtime and the blues. It was however in Europe, where American dance bands were very popular, that composers first incorporated the new American idioms into their classical compositions: Claude Debussy in Golliwog's Cakewalk (1908); Igor Stravinsky in Ragtime (1918); and especially Darius Milhaud in the ballet La création du Monde (1923). George Gershwin was the first American composer to make jazz acceptable to the classical music audience. The performance of his Rhapsody in Blue at the Paul Whitman concerts in 1924 was a groundbreaker. It was however his Concerto in F, commissioned by Walter Damrosch for the New York Symphony and premiered in December 1925, which was the first large-scale jazz composition in a traditionally classical genre. Gershwin, who by that time was already a famous composer of songs and musical comedies, had no experience in orchestration. In the Broadway tradition, this was usually left to professional orchestrators. Even the Rhapsody in Blue had not been orchestrated by Gershwin, but by his colleague Ferde Grofé. But Gershwin took the plunge and orchestrated the Concerto in F himself. The results reveal him as a fast learner. Although billed as a concerto for the concert hall, the Concerto in F adheres only to the most basic elements to classical models for form and structure: three movements, fast-slow-fast. There is no attempt at recreating sonata form in the movements themselves, although the finale is a rondo. In 2003 Jazz pianist Marcus Roberts (b. 1963) made an arrangement of Gershwin’s Concerto for his jazz trio and orchestra. In the process, he greatly expanded the work, with the piano doubling as soloist in the original score and as part of the trio. The trio operates much like any jazz ensemble, picking out the main tunes and freely expanding them. While the solo piano part in the original version already supplies the jazz riffs, its role in the trio adds further jazz treatment – perhaps improvisational – of the themes, as well as considerable length to the concerto as a whole. The trap set adds a new underlying rhythmic component to the orchestral parts. Gershwin employed different jazz styles for the three movements. The First movement, Allegro, employs the quick, pulsating rhythm of the Charleston. The unusual opening is for timpani and trap set, which sets the prevailing rhythm of the movement and announces in no uncertain terms: This is jazz!  The main theme, introduced by the piano, becomes a motto for the entire concerto, recurring frequently in the first movement and in the Finale. In its role as part of the jazz trio, however, it enhances the mood of expectation by riffing on the theme before its unadorned appearance, The main theme, introduced by the piano, becomes a motto for the entire concerto, recurring frequently in the first movement and in the Finale. In its role as part of the jazz trio, however, it enhances the mood of expectation by riffing on the theme before its unadorned appearance,  and after it. and after it.   In addition to developing core thematic material, Gershwin rolls out a series of melodies in contrasting rhythms and moods, expanding each one in the manner of a jazz riff; the first Charleston, In addition to developing core thematic material, Gershwin rolls out a series of melodies in contrasting rhythms and moods, expanding each one in the manner of a jazz riff; the first Charleston,  morphs into a romance for strings in a Latin rhythm. morphs into a romance for strings in a Latin rhythm.  The trio provides its own take on the melody. The trio provides its own take on the melody.  After another Charleston, After another Charleston,  the climax of the movement is a full orchestral repeat of the main theme. the climax of the movement is a full orchestral repeat of the main theme.  The slow second movement has, as Gershwin himself explained, “...a poetic nocturnal atmosphere which has come to be referred to as the American blues...” It is about two big themes, both of which are delayed to produce a sense of expectation that drives the movement and reflect the melancholy sense of longing that characterize the blues in general. Gershwin’s original orchestration gives over nearly half of this movement to the orchestra; it begins with a long introductory section for solo winds, including clarinets, saxophone, trumpet and oboe based on a small rhythmic motive that sets the bluesy atmosphere and contains little hints of the important themes to come.  In this version, however, the trio dominates, adding several minutes of music to the original score. Only after the trio opens the movement, does the wind ensemble get a chance to take over. In this version, however, the trio dominates, adding several minutes of music to the original score. Only after the trio opens the movement, does the wind ensemble get a chance to take over.  In the original version, the piano introduces the main theme, In the original version, the piano introduces the main theme,  but not before the trio has gotten to it first. but not before the trio has gotten to it first.  It even reconstitutes the piano part when playing with the orchestra. The second big theme occurs a full eight minutes into the movement and belongs to the orchestra with only minor emendations It even reconstitutes the piano part when playing with the orchestra. The second big theme occurs a full eight minutes into the movement and belongs to the orchestra with only minor emendations  The Finale, the only movement with a classical structure, is a rondo, actually a toccata, consisting of rapidly repeated notes. From a pop music perspective, the movement is a quickstep.  The first episode brings back in variation the motto from the first movement. The first episode brings back in variation the motto from the first movement.  The theme of the next episode is original to this movement. The theme of the next episode is original to this movement.  In the third episode, Gershwin brings back the main theme from the second movement as a quickstep. In the third episode, Gershwin brings back the main theme from the second movement as a quickstep.  The climax of the movement is a near repeat of the fully orchestrated motto. A rapid coda recalls the rondo theme with a timpani flourish and jazz trill for the horns. The contribution of the trio is to insert riffs on the themes from all three movements, as well as elaborating the original solos. The trap set in particular, plays almost continually, accompanying the solo, trio and orchestra sections. The climax of the movement is a near repeat of the fully orchestrated motto. A rapid coda recalls the rondo theme with a timpani flourish and jazz trill for the horns. The contribution of the trio is to insert riffs on the themes from all three movements, as well as elaborating the original solos. The trap set in particular, plays almost continually, accompanying the solo, trio and orchestra sections.  | ||||||||||

| Copyright © Elizabeth and Joseph Kahn 2015 | ||||||||||